Cosmic rays reveal hidden ancient burial chamber underneath Naples

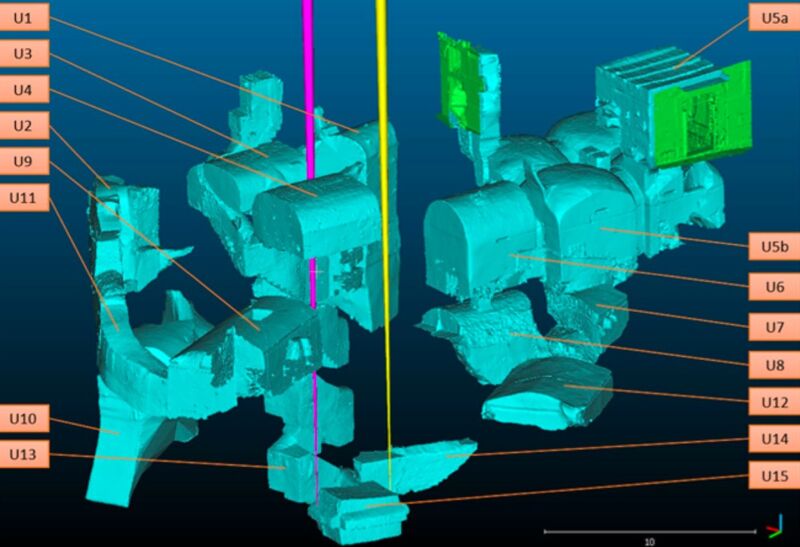

Enlarge / Archaeologists used cosmic rays to detect a secret underground burial chamber from the Hellenistic period in Naples, circa late fourth century/early third century BCE. This is a laser-scanned 3D view of the underground part of the site. (credit: V. Tioukov et al., 2023)

The ruins of the ancient necropolis of Neapolis lie some 10 meters (about 33 feet) below modern-day Naples, Italy. But the site is in a densely populated urban district, making it challenging to undertake careful archaeological excavations of those ruins. So a team of scientists turned to cosmic rays for help-specifically an imaging technique called muography, or muon tomography-and discovered a previously hidden underground burial chamber, according to a recent paper published in the Scientific Reports journal.

As we've reported, there is a long history of using muons to image archaeological structures, a process made easier because cosmic rays provide a steady supply of these particles. An engineer named E.P. George used them to make measurements of an Australian tunnel in the 1950s. But Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez put muon imaging on the map when he teamed up with Egyptian archaeologists to use the technique to search for hidden chambers in the Pyramid of Khafre at Giza. Although it worked in principle, they didn't find any hidden chambers.

Muons are also used to hunt for illegally transported nuclear materials at border crossings and to monitor active volcanoes in hopes of detecting when they might erupt. In 2008, scientists at the University of Texas, Austin, tried to follow in Alvarez's footsteps, repurposing old muon detectors to search for possible hidden Mayan ruins in Belize. And physicists at Los Alamos National Laboratory have been developing portable versions of muon imaging systems to unlock the construction secrets of the soaring dome (Il Duomo) atop the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Flower in Florence, Italy, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi in the early 15th century. The dome has been plagued by cracks for centuries, and muon imaging could help preservationists figure out how to fix it.